Blog and News

Using the Cadence of Prose to Heighten Emotional Impact: Meredith Hall’s Without a Map

- DateMay 10, 2012

- AuthorMary Heather

- Categories

- Discussion0 Comment

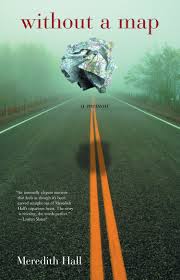

Meredith Hall’s Without a Map is heartbreaking memoir of a young woman who, upon becoming pregnant at age sixteen, is shunned and betrayed by her loving family and close-knit community. Hall, once loved and revered as a model student and promising young dancer in her small New Hampshire town, is expelled from school and kicked out of her mother’s home as a result of her mistake. With nowhere to go, her father and stepmother offer her shelter, but insist that she remain indoors, hidden from the outside world. After her baby is born and given up for adoption, she is banned from her father’s house forever — and left to a life of wandering.

Meredith Hall’s Without a Map is heartbreaking memoir of a young woman who, upon becoming pregnant at age sixteen, is shunned and betrayed by her loving family and close-knit community. Hall, once loved and revered as a model student and promising young dancer in her small New Hampshire town, is expelled from school and kicked out of her mother’s home as a result of her mistake. With nowhere to go, her father and stepmother offer her shelter, but insist that she remain indoors, hidden from the outside world. After her baby is born and given up for adoption, she is banned from her father’s house forever — and left to a life of wandering.

From the beginning, Hall’s story is about shame and loss: the loss of a child, the dissolution of a future, the rejection by one’s peers, and loss of unconditional parental love. Yet despite the odds, Hall cobbles a life for herself, a family of her own, and eventually returns to New England to offer compassion to her aging parents. Then, twenty-one years after her exile, her lost son finds her. As they forge a new path together with her two younger sons, the story evolves from one of grief, to one of joy, wisdom, and understanding.

Hall’s prose in Without a Map is beautiful and lyric, evoking a sadness that won’t let go. Her use of present tense makes the reader live her story, feel the sting of her rejection, and accompany her through the haze of her expulsion. But her beautiful sentences — the detail, the cadence, the movement of her words — are what pierce the reader’s heart. This literary craft blog post examines Hall’s sentence structure in certain places of the text, and how she uses repetition, rhythm, and momentum to enhance the emotional impact of her message.

The first instance occurs in the prologue of the book, “Shunned.” Hall has introduced us to the bones of the story: she was once part of a family and a community, and then she got pregnant. Because of this mistake, she was shunned — ripped away from everything she ever knew and loved. The pain and shock of her rejection is underscored by its contrast against her life until then. She had been an insider, a beloved member of a tight-knit group, as evidenced by the intimate details she knows of those who shunned her:

I still can tell you that Larry had a funny, flat head. That fat Donny surprised us in eighth grade by whipping our a harmonica and playing country ballads. That he also surprised us that year by flopping on the floor in an epileptic fit. That Claudia, an only child, lived in a house as orderly and dead as a tomb. That I coveted her closet full of clothes. That Patty’s father had to drag out muddy, sagging dog back every few weeks from hunting in the marshes; that he apologized politely every time to my mother, as if is were his fault. That Jay wanted to marry me in kindergarten, and that I whipped Jay a year or two later with thorny switches his father had trimmed from the hedge separating our yards. That his father called me Meredy-my-love, and I called him Uncle Leo. That Heather’s grandmother Mrs. Coombs taught us music once a week, the fat that hung from her arms swinging wildly just off beat as she led each song. (p. xi-xii)

Not only do these details validate her standing in the community, the words create a sort of pattern following the beginning of every sentence with the word That. “That Patty’s father had to drag… That Jay wanted to marry… That his father called me Meredy-my-love…” The pattern Hall creates continues for two entire paragraphs — sounding almost like a chant — and produces a rhythm and momentum that carries her readers deeper into her story. We are invested in her story because we have seen first hand how important she once was, and know that this belonging will soon be stripped away.

Hall uses this specific sentence structure again toward the end of the book, when she has returned to New England to care for her ailing mother. In this instance, Hall is overcome with the emotion of seeing her mother suffer from advanced multiple sclerosis, and knows that her mother’s illness eclipses her own need to reconcile their past. For a short time, Hall’s mother improves, and there is a brief window of relief:

Mostly, maybe, of guilt — for my helplessness, for the absolute promise of my own future life, for my desire to turn away from this hideous thing, this wrecker of bodies and lives. Guilt that I have children to raise in happiness and a living to earn and a house to paint and books to read, that I am stretched too tight and tire and breaking from the sadness of watching my mother suffer. Guilt that I feel sorry for myself. Guilt that I cannot fix any part of her rupturing life, that the casseroles I bring and the overnights at my house and the long days at her house with my children are easing and not a cure. (p. 156)

Again, Hall’s repetition of the words guilt, for, and that create a poetic rhythm to the prose, a succession of melancholy waves, with each instance of the word guilt sounding like the toll of a bell. The sound and the feeling of the sentences mirror the emotion Hall is conveying with the details of her words: the pang of her guilt that she is okay while her mother is hurting, and the pain of her own exhaustion from caring for her mother under the weight of their past.

Hall also uses this sentence structure in the end of the book, as she describes her last encounter with her aging father. Having been banned from his house, she no longer knows her father, and recalls him in her childhood memory:

Once, as he sat in the kitchen, my father happily fed toast to our dog, Sam, placing the pieces on the dog’s nose and telling him to wait until he said, “Okay!” Once, my father took us camping at a mountain lake. I cried when I caught a little perch. he cooked it in a heavy black pan over the fire, and we pulled the delicate, pure white skeleton, spine and hair ribs, from the hot flesh. Once, my father hung and skinned a deer he had shot. We children helped scoop the lungs and liver onto newspapers on the garage floor. (p. 196)

The sharpness of Hall’s details, in tandem with her repetitive use of the word, once, create for the reader a more vivid experience. The paragraph reads like a slideshow of intimate family portraits, with the word once triggering each new frame. The effect is clear: Hall’s memory of her father from childhood is sharply contrasted with a man she no longer knows. And having just glimpsed at the family photos — the photos in which Hall was still a cherished member of her family, and her father participated in her life — the reader mourns this loss as well.

Meredith Hall’s Without a Map is an example of how sentence structure can enhance the emotional weight of a story, by creating a poetic rhythm that complements the message of its words. Hall uses this technique to her advantage, making the quality of her prose enrich an already compelling story.

About Mary Heather

I am an East-coaster and a West-coaster. I am an academic and a creative spirit. I am an environmental scientist who always wanted to write, and a writer with a nagging nostalgia for the complexities of environmental science. Above all, I am a mother — so whether I’m writing about the natural world, family, or place, I like to consider my work as environmental advocacy in the broadest sense.

Tags

Recent Posts

- Five Year Mark

- On Writer’s Block: Notes from the Kitchen Island

- The Things They Carried

- Notes from a Soft Target

- On Advocacy and Love

- 2018 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Empathy

- The Fact of a Penis

- Labor Day

- On Hiding

- Memorial Day

- #CNF Podcast Episode 43

- Bay Path University’s 15th Writers’ Day

- On Authority and Punishment

- If There Were No Rules

- Science is a Refugee

- 2017 Moravian College Writers’ Conference

- Thanks, Food & Prayers

- Eviction

- Love Does Not Equal Silence

2014 © Mary Heather Noble. Website Design and Development by The Savy Agency.